- Home

- Cumming, Charles

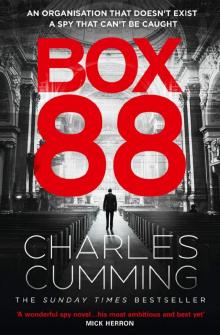

Box 88 : A Novel (2020) Page 14

Box 88 : A Novel (2020) Read online

Page 14

He boarded a train at Euston station just after ten o’clock on Good Friday morning, a day later than he had promised to be home, but there had been a party at Mud Club the previous night which he hadn’t wanted to miss. Kite had taken Ecstasy for the first time, with Xavier and Des Elkins. An older woman who owned her own flat in Lambs Conduit Street had dragged him home but passed out in the living room just as Kite was taking off his clothes. He had no time to sleep. He knew that it would take him at least ten hours to reach Killantringan from London and that his mother would combust if he arrived home any later than Friday night. He checked his wallet, wondering if he could afford to catch a taxi back to Xavier’s house, but realised he had spent every penny he possessed on beer, tequila, two Ecstasy tablets and the price of entrance to the club. He searched the woman’s flat unsuccessfully for loose change – finding a passport in the process which placed her age at twenty-seven – and decided to leave her a note. Still high, still hoping that one day he could come back here and go to bed with her, Kite found a sheet of paper in a kitchen drawer and scribbled: Hi Alison. You fell asleep. Sorry I had to go but I live in Scotland and need to catch a train. Heading home today. It was really great to meet you. Lachlan x. He wrote down the number of the hotel but began to worry that if Alison called during the Easter holidays, his mother would answer and let slip that her son was only eighteen years old. It was worth the risk. Kite left the note on the kitchen table and crept out into the street.

It took him an hour and a half to walk from Fitzrovia to Kensington, the last of the Ecstasy wearing off as he passed the Victoria & Albert Museum. He arrived at Xavier’s house in Onslow Square just after seven o’clock. Xavier had made it home from Mud Club and was asleep in his clothes upstairs. His mother had bought him a black leather jacket almost identical to the one worn by George Michael on the cover of Faith. Xavier, who was sprawled on his bed in artfully-torn, stonewashed Levi 501s and a white T-shirt, had left it on the back of a chair. Kite went through the pockets, borrowed sixty pounds from Xavier’s wallet, took a shower, ate a breakfast cooked by the Bonnards’ Filipina maid and set off for Euston. As soon as the train had pulled out of the station he fell asleep in his seat, waking only once during the five-hour journey to Glasgow to buy a bacon roll and a much-needed bottle of water.

The first anomaly of that unusual Easter weekend occurred on the coastal train to Stranraer. Kite had boarded the service at Glasgow Central, having called his mother from a phone box to tell her that he would be home by nine.

‘Where the hell have you been?’ she asked, the sound of a second telephone ringing in the office beside her. Fifteen years in hospitality had softened her accent, but a trace of the East End was always detectable, especially when she lost her temper.

‘It’s OK, Mum,’ Kite replied, feeling oddly numb as he cupped his hand over the receiver to smother the noise of the station. ‘I had to go to a birthday—’

‘It is not OK, Lachlan. You promised me you’d be back last night and I had no way of contacting you. I didn’t even know where you were staying—’

‘I always stay with Xav—’

‘I’ve got thirty guests in the hotel, another twenty for dinner tonight. Mario turned out to be a bloody thief, so there’s nobody here to take orders in the restaurant. I’m simultaneously trying to run the bar, ferry food from the kitchen to the restaurant, turn down the beds upstairs and keep a bloody smile on my face for the guests.’

‘I’m sorry, I’ll be back—’

‘Just get here.’

Cheryl had hung up before her son had a chance to ask if someone might collect him from the station in Stranraer. Shortly afterwards, having sunk a hangover-busting can of Irn Bru and bought a copy of the NME at John Menzies, he boarded the service to Ayr.

It was a damp March evening on the west coast and the smell of the sea seeped through the train, telling Kite that he was home. He sat in an almost-empty carriage towards the back of the train, ticking off the towns through rain-streaked windows: Kilwinning, Irvine, Troon, Prestwick. These were the places of his childhood: grey, lifeless settlements a million miles from the dreaming spires of Alford and the wild child hedonism of Mud Club, Crazy Larry’s and 151 on Kings Road. Kite didn’t know much about ship-building on the Clyde or the coal industry in Ayrshire, but he knew that whole communities had been eviscerated by a decade of Thatcherism, two generations of men left without work or purpose. It may have been his hangover – too little sleep and the after-slump of Ecstasy – but at that moment he felt a raw sense of separation from the country of his birth. It was as if he had left Scotland in 1984 as one sort of person and was returning, for the final time, as quite another. In London, surrounded by girls and Pimm’s and parties, Kite and his friends tried to emulate the deracinated, coke-addled hipsters in Bright Lights, Big City and Less Than Zero; rolling towards Killantringan on an empty British Rail train defaced by litter and graffiti, he did not know who he was or what he was meant to be. The dutiful son to a demanding mother? The secret posh boy pretending to be a ‘normal’ Scottish teenager? He wondered if all of the privilege he had witnessed at Alford – the country houses, the Bentleys parked by chauffeurs on the fourth of June, the skiing holidays in Verbier and Val d’Isère – would become commonplace to him, a day-to-day feature of his adult life. Or perhaps Alford would prove to be just a blip and Kite would return to the world of catering and hospitality, graduating from Edinburgh University in four years’ time to help his mother with whatever venture she took on after selling Killantringan.

The trouble started in Ayr where Kite had to change trains. He was obliged to wait on the platform for the service south to Stranraer. A group of three local youths in their early twenties were ragging around in the waiting room, smoking Embassy cigarettes and sharing a half-bottle of Smirnoff. They were wearing tracksuits and trainers and quickly clocked Kite – with his foppish public school haircut and collared shirt – for an outsider. The tallest of them, the ringleader, had a wraparound tattoo on his wrist which spread all the way up to his armpit. He flashed Kite a vicious stare and pointed at his bag.

‘What’s in there, big man?’ he called out from the waiting room.

Kite wasn’t afraid of him but knew that if it came to a fight, he was outnumbered.

‘Kittens,’ he said, immediately finding his old Scottish accent so that ‘kittens’ sounded like ‘cuttens’.

‘What’s that? You making a joke, pal? You making fun of me and my boys?’

Kite shook his head slowly, felt his heart thump and said: ‘Nah. Don’t worry.’

‘You’re a funny man? Is that it? Telling me you got kittens in yer bag when you don’t?’

Kite wondered why the hell he had said something so stupid.

‘Relax,’ he said. ‘We’re all waiting for the same train. I thought it would make you laugh.’

Kite was worried that his accent would slip, that he’d pronounce certain words in an English way and reveal his secret life in the south.

‘I’m very relaxed,’ said the leader, looking to his left, where the older of his two companions, a short, muscular skinhead, was rolling a cigarette. ‘Pete, are you relaxed?’

‘Aye, Danny.’

‘Robbie, are you relaxed?’

‘Aye, Dan. Very relaxed.’

There was nobody else on the platform. Just Kite standing outside a waiting room being sized up by three drunk Scots who would likely beat him up and steal his Walkman if they had the chance. Kite moved further along the platform, but Danny saw this and followed him, Robbie and Pete close behind. It was like being surrounded by a pack of hyenas on the scent of their prey. Kite knew that he couldn’t run, that it was important to stand his ground, but he had heard stories of flick knives and muggings and wondered what it would take to make them walk away.

‘Got a smoke, pal?’ said the leader, coming right up into his face. He had a gold stud earring in his left ear and a Beastie Boys VW necklace. His breath stank of alco

hol. Kite winced as he thought of his father.

‘Maybe,’ he replied.

At that moment, the Stranraer train came south through the sea mist hanging low over the tracks. Nobody spoke as it drew in beside them. There were four carriages, all seemingly empty. Kite had a packet of Marlboro Reds in his jacket pocket but reckoned Danny would grab the whole thing if he took it out and offered him one.

‘Where you off to, big man?’

‘Stranraer,’ Kite replied, forgetting how to give the name a Scottish inflection. ‘You?’

‘None of yer’ fuckin’ business, ya’ cunt.’

They were standing between two of the carriages. Kite felt his chest contract and walked to the left, expecting the youths to follow him, but either Robbie or Pete – Kite couldn’t tell which – suddenly hissed and whispered: ‘Hang on, Dan. Check this.’ To his surprise they then boarded the carriage next door, laughing gleefully as they did so, leaving Kite alone. Something must have caught their eye: a new target, a new figure of fun. He felt a wave of relief, particularly when he saw that there was an elderly man a few seats away reading the Glasgow Herald. There surely wouldn’t be any trouble while he was around. He wouldn’t let an eighteen-year-old kid get beaten up in plain sight. Kite was safe. The train pulled away from the platform and he sat down.

Then the situation deteriorated.

Through the doors that separated Kite’s carriage from the rear of the train, he could see the three young men gathered around a table. They were speaking to somebody. Pete was on his feet, laughing and swigging from the bottle of Smirnoff. Danny and Robbie had sat down. Kite saw that they were talking to a young black woman. A non-white face on the west coast of Scotland was as rare as a non-white face in the classrooms and playing fields of Alford. They had chosen their next target.

Kite stood up and looked more closely through the doors. The woman was trapped at the table with Robbie beside her and Danny in the facing seat. She was about thirty and looked frightened. Kite checked the rest of her carriage. There was nobody else around. He was tired and hungover and dreading the long Easter shift ahead of him, but knew that he had to do something. His father would have expected it. It was the way Paddy Kite had raised his son.

‘Excuse me,’ he called out to the old man. His Alford accent had returned. He hadn’t bothered to smother it. ‘I think a woman might be getting hassled next door. Will you keep an eye on me?’

The old man, who was wearing a black anorak and a cloth cap, barely acknowledged what Kite had said. He didn’t want any trouble, didn’t want to get involved. Kite shouldered his bag and opened the first of two connecting doors. The train rocked through a set of points and he almost lost his balance as he opened the second door and entered the carriage. He heard Robbie saying: ‘No, come on. Where are you from, darlin’?’ as he was hit by a rancid smell of stale vomit and spilled beer. Pete had now sat down. The woman was surrounded.

‘How’s it going here?’ Kite called out as casually as possible, finding his Scottish accent. ‘Everything OK?’

Danny was startled to see Kite coming towards him. Kite put his bag on a nearby seat, removed the set of Walkman headphones from his neck and zipped them inside an outer pocket.

‘You asked me for a cigarette,’ he said, tapping his jacket. ‘I found some more.’

He looked at the woman. It was impossible to tell from her expression if she was relieved that Kite had come to help her or if she believed that he was a friend of the men who had surrounded her and was coming to join in the fun.

‘We’re OK thanks, pal,’ Danny replied.

‘So what’s going on?’ Kite asked. ‘Are you all friends?’

He was beside the table now, a sheen of sweat inside his shirt, his heart racing, but determined not to appear scared or weak.

‘No. Are youse friends?’ Danny asked.

‘She your sister?’ Robbie added, and the three hyenas erupted in laughter.

Kite decided to speak to the woman directly.

‘Are you OK?’ he said.

She was too frightened to reply.

‘You still havenae told us where you’re from, darlin’,’ said Pete, ignoring Kite as he finished the last of the vodka. Kite could feel Danny bristling and looked down at his tattoo. He wondered what it would feel like to be punched by an arm that size. There were three black students out of twelve hundred and fifty boys at Alford. One was the son of an African politician, another an American from New York, the last a scholarship boy from London. During a football match in 1987, Cosmo de Paul, whose grandfather and great-grandfather had been at the school, had called him a ‘fucking nigger’ but had not been expelled. Kite thought of that now as he tried to defuse the situation as best he could.

‘If you don’t know her,’ he said, ‘why are you hassling her?’

‘Hassling her?’ said Danny, making a mockery of the word. ‘How come it’s your business anyway, you posh cunt?’

‘I don’t like bullies,’ Kite replied, suddenly very frightened. He was amazed, and oddly humiliated, that he had been identified as posh. If any of these men was carrying a knife they surely now would not hesitate to use it.

‘I don’t give a ratsy fuck what you do and do not like, pal, ken?’

‘Leave him alone,’ said the woman. She had a pronounced West African accent and a desperate look in her eyes.

There was a collective sarcastic sigh, then a long romantic ‘ooooh’ as the three men mocked what she had said. Pete made a kissing sound with pursed lips. A wild, joker’s grin spread out across Danny’s face. Robbie gleefully shouted: ‘They’re in love, Dan. He fancies a fuckin’ black bird.’

Kite was breathing the vodka, the same nauseating chemical stench he remembered smelling a hundred times on his father’s breath. He knew that he only had to survive for another three or four minutes before the train reached the next stop at Maybole and he could get help. There might be more passengers on the platform, perhaps a stationmaster who could get the situation under control.

‘It’s sad what’s going on here,’ he said, trying to reassure the woman with his eyes.

Again Danny pounced on his choice of words.

‘Sad, is it? Are you gonna cry? Is that what’s gonna happen, ya’ fuck?’

If Kite had been less hungover, if there had been two of them, not three, if he had been sure that they weren’t carrying knives, he would have thrown a punch at this moment, just as he had decked Richard Duff-Surtees three years earlier with a sweet right hook at fly-half. But his physical courage deserted him. He knew that he was going to have to stand his ground and try to win the fight with patience and words.

‘I’m not going to cry,’ he said. ‘I’m not frightened by you. I think you’re the ones who are weak. What’s a woman on her own supposed to do when—’

‘A black woman, mind,’ Robbie interjected, but his response sounded oddly feeble.

Pete began to sing the refrain from an advert Kite had seen on the TV for fruit juice: ‘Um Bongo, Um Bongo, they drink it in Um Congo.’ Robbie laughed wildly at this and joined in, saying: ‘Aye, she probably wants a banana.’

‘It doesn’t matter where she’s from or what colour her skin is,’ Kite answered, watching Danny very carefully because he was waiting for him to stand up and strike. ‘There’s three of you. One of her. She’s not causing trouble. Pick on someone else.’

As if Kite had pressed a button, Robbie and Pete immediately stood up out of their seats and turned to him, Danny doing the same and saying: ‘OK, big man. We’ll pick on you then.’

‘No!’ the woman shouted, but she did not move from her seat. Kite backed away, praying that the train, which seemed to be slowing down, was coming into Maybole. The three men had formed a sort of column and were following him towards the back of the train, closing down the space. Kite couldn’t go left. He couldn’t go right. He was trapped. Danny hawked up a ball of phlegm from his lungs and spat it at his feet.

‘Tickets please,

gentlemen!’

All of them looked towards the front of the carriage. A ticket inspector had entered at the far end. He was at least fifty and recognised immediately that there was a problem.

‘What’s goin’ on here?’ he shouted.

‘Fuckin’ nothing, man,’ Pete muttered.

‘Just havin’ a wee chat with our pal here,’ said Danny.

They scuttled back like boys caught smoking cigarettes in the woods at Alford, all blank faces and innocence, leaving Kite with a decision either to grass them up or hope that they left the train at Maybole.

‘Are you all right?’ said the inspector. The woman had come out from behind the table and was standing near the central door of the carriage.

‘I’m fine,’ she said. ‘Everything’s fine.’

Kite saw the lights of Maybole up ahead. He had never been more relieved in his life.

‘You getting off here?’ the inspector asked. He had directed the question at the woman, but Danny said: ‘Aye, we’re getting off. Nay bother.’

‘My husband is meeting me,’ the woman answered, loud enough for the youths to hear.

Kite realised he was in the clear. Everyone was leaving. The woman would be safe in Maybole. Her husband was probably waiting for her on the platform.

‘OK,’ said the inspector. ‘So let’s get going, gentlemen, please, before I find out any more about what was happening here. Gather your belongings and be on your away.’

Laughing and jostling one another, without a further word either to Kite or the woman, the men opened the door onto the platform and stepped off the train. The woman waited until they were several metres away then spoke to Kite.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘You were very brave.’

‘No problem,’ Kite replied. He felt a wave of satisfaction as euphoric as the first surges of Ecstasy on the dance floor at Mud Club. ‘Take care of yourself.’

A white man in a business suit was waiting on the platform, looking up expectantly. Very slowly, the woman stepped down from the train and walked towards him. As he hugged her, Kite saw the woman begin to sob as she slumped in his arms. The ticket inspector turned to Kite.

Box 88 : A Novel (2020)

Box 88 : A Novel (2020)