- Home

- Cumming, Charles

Box 88 : A Novel (2020) Page 12

Box 88 : A Novel (2020) Read online

Page 12

‘Must have,’ said Vosse wistfully. Tomkins wondered why he sounded disappointed. Surely this was the boss’s chance to go home and get a few hours’ sleep? ‘All right then. Keep your eyes peeled. Call me if anything changes. I’m not going home, I’ll sleep here in Acton. Eve and Villanelle will be there at seven to see what comes next.’

It was only when Vosse had hung up that Tomkins understood the nature of the boss’s frustration: he had been hoping that Zoltan would slip up and lead him straight to the Iranians. That seemed naive. A MOIS team weren’t going to allow a man like Pavkov to make such a basic mistake. No, if Five were going to find Lachlan Kite, they were going to have to do it the hard way. That meant Tomkins sitting on his arse in the driving seat of a banged-up Ford Mondeo for the next nine hours while everyone else on the team got some precious sleep. Tomkins felt the injustice of his predicament as a personal slight. What the hell had he done to merit working the night shift? Why was it always Cara who got the sweet gigs – dressing up and going to the funeral – while he was forced to sit around and wait and pick up the dregs of the operation? It wasn’t even as if Zoltan was particularly useful to them. Tomkins was 99 per cent certain that the Iranians were going to kill Kite. On that basis, everything he did for the next nine hours – the next nine days, the next nine months – would likely be a complete waste of his time.

He sat back and looked down at the tablet on the passenger seat. If Pavkov made a call or sent a text, the screen would let him know. If he didn’t, it wouldn’t – and Tomkins didn’t expect it to. He was wearing AirPods which picked up sound on the microphones inside the flat; they also allowed him to answer incoming calls from Vosse. The earpieces left a permanent low static hiss in Tomkins’s ears, as well as occasional clicks and snaps of feedback, all of which intensified his annoyance and frustration. While Cara slept a soundless sleep less than two miles away in Hackney Marshes, Tomkins was getting cramp in a stakeout Mondeo with no music to listen to and a Serbian migrant across the street more likely to invite his neighbours round for an all-night barbecue than he was to get on the phone and contact the men who had kidnapped Lachlan Kite.

Tomkins looked up at Zoltan’s one-bedroom flat on the second floor of the rundown, Brutalist residential block that the Serbian called home. In a way that he couldn’t fully explain to himself, because he had read a lot of books and talked to a lot of intelligent, liberal people, Matt Tomkins didn’t like Serbians. When he had first heard the name ‘Zoltan Pavkov’ from Vosse that afternoon, he had instantly felt a mixture of threat and resentment. It was the same with Bulgarians or Albanians or Romanians: Tomkins’s guilty secret was that he didn’t like any of them, male or female, young or old. In the same way that his father thought the country was full and there were too many foreigners clogging it up, Tomkins didn’t think that anything good or constructive could come from allowing too many more Serbians or Albanians or Romanians to settle in the United Kingdom. He realised that it was wrong to think and feel this way – that it was actually illegal to think and feel this way – but he couldn’t help himself. He would be fired from MI5 if anyone ever found out. Tomkins wasn’t proud of the fact that he resented men like Zoltan Pavkov for taking the UK for a ride, but he secretly hoped to find someone discreet at work – perhaps even a small group of like-minded people – who shared his views.

Tomkins hadn’t yet seen Zoltan in the flesh, but he already knew, just by the general tenor of his conversations with Cara and Vosse, that he was lazy and corrupt and unreliable. Look at the facts. He lived in a shitty one-bedroom flat in Bethnal Green. He drove an illegal third-hand Fiat Punto which would probably blow a tyre and cause an accident if it went any faster than fifty miles per hour on a dual carriageway. He had taken money from MOIS to facilitate the capture of a suspected British intelligence officer and doubtless enjoyed dishing out £250 fines to customers in his car park who turned up five minutes late to retrieve their vehicles. What was the fucking point of someone like Zoltan Pavkov being allowed to remain in this country? He was just the right age to be a Balkan war criminal, an associate of Mladic´ or Karadžić, a soldier party to mass slaughter in Bosnia who had somehow tricked Britain into giving him political asylum, then Right to Remain, then a passport entitling him to exactly the same lifestyle as Londoners whose ancestors had lived in Bethnal Green for three hundred years.

‘Chill out,’ he whispered, aware that he was allowing himself to become agitated. ‘Just chill.’

Tomkins took out his personal mobile and saw that he had received a couple of text messages, one from his mother, the other from a girl he had met on Tinder who didn’t know how to read the signals and kept bugging him to meet up, even though she was much fatter than her profile photos and there had been zero chemistry on their one and only date. He was about to start flicking through Tinder, a few left and right swipes just to kill some time and put him back in control, when something caught his eye at the entrance to Zoltan’s building.

A light had triggered. Somebody was coming out of the street door carrying a plastic bag and wearing what looked like a beanie. It was a man. He was short and stooped and – from a distance of sixty metres – seemed to match the description Tomkins had been given of Zoltan Pavkov.

‘Fuck,’ he whispered. His whole upper body tensed up. How had he missed this? No lights had come on in the flat. There hadn’t been a whisper through the AirPods. Then Vosse rang.

‘Hello?’ said Tomkins, aware that his voice sounded dry and nervous.

‘Situation,’ Vosse replied. No question mark in the numb inflection of the word, no ‘Hi’ or ‘How are you doing?’ Just ‘Situation’, as if Tomkins was a robot, a kind of MI5 version of Alexa, sitting in a car at one o’clock in the morning waiting to do the bidding of Robert fucking Vosse.

‘Excuse me, sir?’

‘I said situation, Cagney. What’s it looking like? Where is our man? Still asleep? Watching Belgrade Tonight on the telly? Taking a much-needed shower? Any sign of him in the last ten minutes or can I go to sleep?’

‘I think someone just came out, sir. I think it might be him, but I didn’t hear anything on the micro—’

Vosse’s response was explosive.

‘What?’ he said. ‘You think someone just came out or you know the target is mobile?’

Tomkins looked again. The man in the beanie had stopped on the far side of the street. He was taking something out of his left trouser pocket. If a vehicle came towards him and Pavkov happened to look in Tomkins’s direction, his face would light up in the front seat of the Ford like a Halloween pumpkin.

‘I’m sure it’s him,’ he said, trusting his instinct. ‘Woollen hat, like you said he was wearing in the car park. Same features, same height. It’s a match.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I’m telling you now. It only just happened when you rang.’

Tomkins worked out what was going on: either Zoltan was heading to a prearranged meeting or he had a burner phone inside the flat which he had used to contact the Iranians.

‘Looks like he’s going for his car,’ he told Vosse, catching the glint of a streetlight on a set of keys in Pavkov’s left hand. The target walked away from the Mondeo in the direction of his own vehicle, parked thirty or so metres further away down the street.

‘You need to follow him,’ said Vosse. ‘I’m blind here. All I’ve got is the microphone in the Fiat. The trace is dead.’

Tomkins was horrified. He lifted the tablet from the passenger seat and keyed through to the live feeds from Zoltan’s Fiat Punto. He could see what Vosse could likely see on his own screen in Acton: a descriptor for the dashboard microphone implanted that afternoon, but no signal from the GPS.

‘What happened to it?’

‘Fuck should I know? Happens too often. These people have one job – give me a trace that works – and they can’t do it.’

‘Battery must have failed.’

‘You think?’ said Vosse with too

much sarcasm for Tomkins’s liking. ‘What’s his position?’

It was pitch-dark on the street and Zoltan had briefly vanished behind a line of parked cars. It occurred to Tomkins that carrying the keys might be a bluff for surveillance: the Iranians could be waiting for him in a second vehicle on an adjacent street. Should he follow on foot or remain in the Mondeo? Why the hell had Vosse left him on his own? Why wasn’t Cara here in a backup car instead of fast asleep in Hackney Marshes?

‘One zero zero metres down the street. Carrying a plastic bag. Interior lights in the Fiat just came on.’

Zoltan was getting into his car. Tomkins quickly checked the tablet to see if any messages had been sent or calls made from the Serb’s mobile but the read-out was predictably blank.

‘What’s in the bag?’ Vosse asked.

Tomkins tuned the AirPods to the mikes inside the Fiat and said: ‘I don’t know yet, sir.’

‘Don’t fucking lose him, Cagney. I don’t have a fix on whatever phone he’s using. There are no other eyes on this except yours. It’s old school. No triangulation.’

‘I understand that,’ Tomkins replied.

He was determined to succeed – to follow Zoltan discreetly, to work out where he was going, to lead Vosse to the Iranians – but at the same time Tomkins was overcome by self-doubt. He knew that he didn’t yet possess the skill to tail a moving car without giving himself away. Pavkov was acting in a clandestine manner. He was finally aware of a threat from surveillance. Why else go to the trouble of keeping the lights off inside his bedsit and slipping out in the dead of night with a carrier bag containing who knows what?

‘Can you hear that, sir?’

The mikes in the Fiat had caught the sound of Pavkov rustling around in the bag. Tomkins lowered the volume on the AirPods to stop them deafening his eardrums. He frowned as he concentrated on the noises, trying to pick out what was happening.

‘I can hear it,’ said Vosse. More rustling of plastic, then the noise of something hard banging against a pane of glass. ‘What can you see?’

It was against all protocol to sit inside a stationary surveillance vehicle and to train a set of binoculars on a target, but Tomkins did exactly that. He needed an advantage.

‘He’s doing something to the dashboard,’ he told Vosse, adjusting the focus.

‘Fuck. Taking out the microphone?’

‘Don’t know, sir. Unclear.’

The banging and the clattering and the general rustle of plastic continued. Tomkins saw the Serbian repeatedly reach forward towards the windscreen, as if he was trying to attach or remove a sticker from the glass.

‘Wait. I’ve got it.’

He again adjusted the focus and Zoltan’s head became crystal clear. The Serb had left the lights on inside the Fiat to help him carry out whatever task he was trying to complete. That was when Tomkins saw the pale blue glow on the screen of a TomTom. Pavkov was busily attaching it to the windscreen.

‘I think it’s a satnav, sir.’

‘Say that again.’

‘An old-fashioned TomTom. A GPS. He doesn’t have a smartphone so he’s using it for directions.’

‘Good for him,’ said Vosse. ‘But where the fuck is he going? Doesn’t help us if he’s navigating by the stars or being drawn in by smoke signal. We still don’t know his destination.’

Tomkins started the engine on the Ford Mondeo. He had only passed his test eighteen months earlier and wasn’t a particularly experienced driver. He had lived in London for the past four years and went everywhere on public transport. If Pavkov ran a red light or got away from him on a dual carriageway, Tomkins didn’t trust himself to be able to keep up.

‘He’s pulling out, sir,’ he told Vosse, leaving his headlights off for as long as possible so that Zoltan wouldn’t see them flare in his rear-view mirror. ‘Maybe Lacey could help? You could wake her up.’

‘Fuck that for a game of soldiers,’ said Vosse. ‘This thing will be over in less than ten minutes. You just stay on his tail, son. You don’t let that bastard out of your sight.’

14

Kite had fallen asleep in his blacked-out cell.

He was dreaming of Martha Raine when he heard the key turning in the lock. He woke in the darkness to Isobel’s face staring at him from across the pillow, the mirage disrupted by a burst of light from an opened door.

‘Time to get up,’ Torabi shouted. He was standing next to Strawson. ‘WHO WAS BILLY PEELE?’

‘What?’ said Kite, sitting up. He was sweating and the lights had gone out. He said: ‘Torabi?’ into the room but there was nobody there.

Kite had dreamed it all: Martha and Isobel, Strawson and Torabi, twisting through his unconscious mind like a helix. He reached down for the plastic bottle and drank some water. He had no idea of the time, no idea how long he had been asleep. He lay back on the bed and closed his eyes. He could still hear Torabi’s voice in the fever dream:

Who was Billy Peele?

He was my teacher, but he was more than a teacher.

He was the brother I craved, yet he was not my brother.

He was a father when I had no father. He was my guide and instructor – and every young man needs a mentor.

Billy Peele was everything to me.

* * *

Three days have passed since Xavier has issued Kite with his seemingly innocuous invitation to spend part of the summer holidays at his father’s house in Mougins.

The two friends are in a low-roofed, prefabricated Alford classroom at the edge of the school campus, close enough to the racquets building to hear the exhilarating metallic contact of the ball as it echoes and strikes against the stone walls of the court. It is a piercingly clear February morning, nine boys in tailcoats awaiting the start of Double History with William ‘Billy’ Peele. Cosmo de Paul, who has already taken the Oxbridge exam and requires only two E grades at A level to secure his place, is among them. De Paul is wearing Pop trousers and a Salvador Dalí waistcoat purchased for him by his mother in honour of the recently deceased Catalan surrealist. Leander Saltash, soon to be Kite’s opening partner in the cricket first XI, is also in the room, as is Kite’s friend, Desmond Elkins, who will be killed fighting for the SAS in Afghanistan fourteen years later.

Peele, as always, is late. The boys, all approaching or past their eighteenth birthdays, are too old to be flicking ink or throwing balls of paper around the classroom. Instead they pass the time boasting about the girls they have snogged at a recent Gatecrasher Ball and the quantities of ‘snakebite’ they consumed at the weekend in ‘Tap’, the school pub in which boys are permitted to drink alcohol. At ten to twelve, there is the familiar approaching squeak of Peele’s under-oiled bicycle, then a clatter as it topples over outside the classroom. The boys mutter, ‘He’s here’ and return to their desks, looking up in expectation of the great man’s arrival.

Seconds later, Billy Peele bursts through the door.

‘Gentlemen,’ he proclaims. ‘I am here to tell you that the most famous spy in the world has fallen off his perch.’

In one continuous movement, Peele slams the door behind him with the heel of his boot, places a pile of books and essays on his desk, removes a black beak’s cloak with the flourish of a matador wielding a cape at Las Ventas and spins it onto a nearby hook.

‘The name is no longer Bond, James Bond, gentlemen. Double 0 Seven is dead.’

Peele’s head snaps through ninety degrees, scanning the classroom of sleep-deprived students for a reaction to this astonishing newsflash. He is a physically fit, bearded thirty-eight-year-old with tortoiseshell glasses and his uneven, hastily assembled beak’s bow-tie looks as though it could do with a wash.

‘Is Timothy Dalton dead?’ asks one boy.

‘Good,’ Xavier declares. ‘He was shit in Living Daylights.’

‘Language please, Monsieur Bonnard,’ Peele grumbles. ‘Language.’

‘Not Dalton,’ says another student, who will later go on to become MP for North Dors

et and a vocal proponent of Brexit. ‘Got to be Connery or Roger Moore. Is it one of them, sir?’

An exasperated sigh from Peele, Kite enjoying the show from the back row.

‘Don’t be so literal, Williams.’ Peele cleans the whiteboard with an ink-stained Charles and Diana T-towel and clears what sounds like forty overnight Gauloises from his barrel chest. ‘Think beyond the proverbial envelope. I said he has “fallen off his perch”. An ornithological clue with an old Alfordian link. Any bright sparks out there with the faintest whiff of an idea what on the planet Pluto I’m talking about?’

A sustained silence. Lachlan Kite is as much in the dark as everyone else. To his right, Cosmo de Paul is arranging his books and stationery into neat piles, anxious for the class proper to begin. A levels are scheduled to kick off in less than three months and he wants straight A’s for his CV. Peele, in common with every other A-level beak in the school, is supposed to be cramming the boys with every spare minute available.

‘Bueller?’ says Peele, mimicking the lifeless, energy-sapping teacher in the John Hughes movie and showing off a passable American accent in the process. ‘Anyone …? Bueller …?’

At last a hand shoots up, two rows from the front. It is Leander Saltash, who has read every thriller of the last hundred years, from The Riddle of the Sands to The Silence of the Lambs, from The Hunt for Red October to The Last Good Kiss.

‘I’ve got it, sir. Not the James Bond of the films but the James Bond of the books. The birdwatcher whose name Ian Fleming stole when he was writing Casino Royale. Is that right?’

‘Mr Saltash!’ Peele bangs a fist on the desk so that two marker pens jump and then roll onto the ground. ‘An excellent answer! If you’re not running the country by the time you’re forty, consider your talents to have been wasted. You would look slightly less fetching with a blue rinse and a handbag than our dear Mrs Thatcher, but it seems a small price to pay.’ Sudden eye contact with Kite, a knowing, private glance of the sort Peele bestows on him from time to time. ‘Yes, James Bond, the original James Bond, American ornithologist and author of that page-turning classic, Birds of the West Indies – kites included, no doubt, Master Lachlan – whose seemingly mundane, commonplace name was indeed adopted by Ian Fleming – late of this parish – for the hero of his bewilderingly successful series of espionage capers. This is the man who has indeed gone to the great birdbath in the sky. May he rest in peace.’

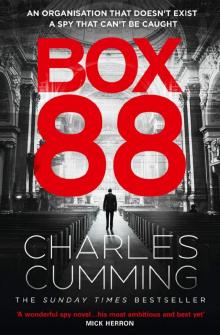

Box 88 : A Novel (2020)

Box 88 : A Novel (2020)